February 28, 2022

Andrew Forrest’s impassioned denouncement this week of all hydrogen derived from coal was an oddly loose contribution to the energy debate – even accounting for Twiggy’s taste for vaudeville.

In calling on the Australian Government to abandon support of all forms of hydrogen extraction that don’t align with Fortescue’s new green hydrogen investments, Mr Forrest suggested that using “decaying swamp matter” (aka coal) to extract the gas would cause Australians to look like “zero-IQ idiots” and constitute a “cringe-inducing backwards shuffle into the dark ages.”

It never fails to surprise me how quickly the energy discussion seems to ramp up into hyperbolic moral declarations of pure good and evil. In my experience, it’s generally useful to contrast rhetorical flourishes with facts.

Hydrogen, which produces zero carbon emissions when burnt, can be produced in a number of ways.

The most common and cheapest type of hydrogen we have now is generally known as “grey hydrogen.” It is made from methane – natural gas. The next cheapest is often referred to as “brown hydrogen” and is made from oil or coal.

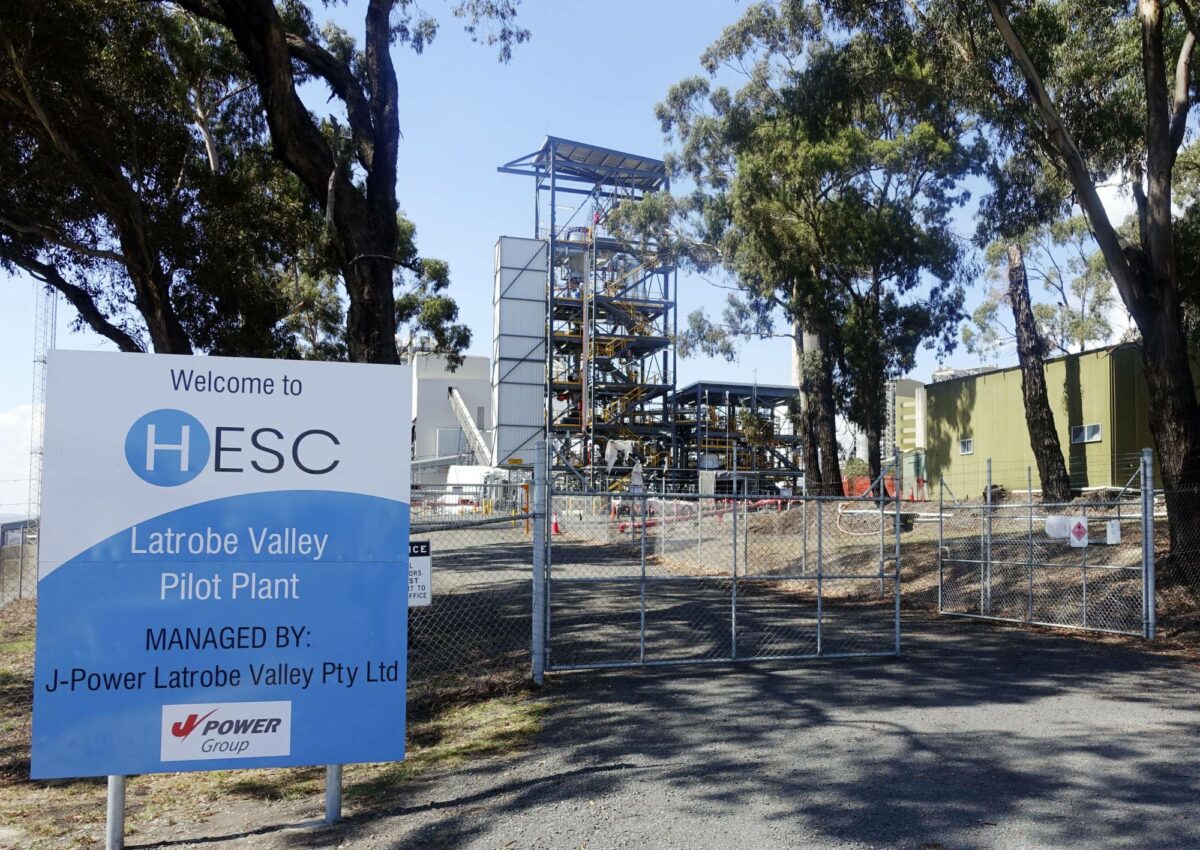

Producing hydrogen this way creates carbon dioxide. This is why there has been so much investment in CCS (carbon capture and storage) technology to prevent emissions from entering the atmosphere. The results get called “blue hydrogen”, and this is what’s being piloted in a $500m project in the Latrobe Valley to generate hydrogen from the region’s abundant brown coal resources.

Mr Forrest is keen to write CCS off entirely based on the fact that Chevron’s Gorgon CCS project has only managed to store a million tonnes a year of CO2, instead of the four million tonnes it projected.

I don’t think such blunt dismissal is warranted. New technology takes time and investment to develop. All the indicators are that the Latrobe Valley initiative will successfully store CO2 deep underground in the Gippsland Basin.

Mr Forrest argues such projects should be abandoned in favour of “green hydrogen,” produced by pumping enormous quantities of renewable energy into water and splitting its molecules. The problem is that green hydrogen is nowhere remotely close to economic – costing well over US$8 per kilogram, many times the cost of grey hydrogen. So presumably Mr Forrest would like us to offer green hydrogen technology more patience than he is prepared to grant CCS.

Hydrogen has a range of exciting potential applications. You most commonly hear about it as a back-up to renewables, to keep electricity flowing when the sun doesn’t shine and the wind doesn’t blow. However, it has applications much closer to home for Mr Forrest, because it can potentially be used to replace the coking coal used to turn iron ore – which has made Twiggy the richest man in Australia – into steel.

Now, the gap between the cost of using coking coal to make steel and hydrogen is vast and will remain so for a long time. But given that in FY20 alone the manufacture of steel in China with Fortescue’s iron ore caused 241 million tonnes of carbon emissions – more than all the combined annual emissions of Australia’s export thermal coal sector – you would think Mr Forrest may be more open-minded about efforts to progress the hydrogen industry.

Waiting for Fortescue’s “green hydrogen” initiatives to become viable could take an extremely long time, presuming they ever come to fruition at all.

This is not to criticise green hydrogen itself. Technology will advance and it will play a role in the future. The question is how best to get there.

We could wait patiently for Twiggy to deliver on the quantum leap he promises. Or we could heed the more pragmatic advice issued recently by Blackrock CEO Larry Fink in his annual letter to CEOs in which he noted “we need to pass through shades of brown to shades of green.”

I would argue that you can’t create a hydrogen economy without supplying affordable hydrogen. We need cheap hydrogen to start with and brown coal is the most cost-effective feedstock. The idea of the Japanese pilot project in the Latrobe Valley is to try producing and transporting affordable hydrogen. It is testing whether we can manufacture hydrogen, store it, truck it to Port Hastings, chill it to -253 degrees, and put in on boats. Can the Japanese then ship it internationally and build and run plants that burn hydrogen safely and economically? Does the whole complex process work? It will be one of many pilot projects to solve these and a host of other challenges.

I think the arrival of the Japanese vessel Suiso – the world’s first carrier of liquified hydrogen – in Port Hastings to pick up its first shipment from the Latrobe Valley pilot plant is an exciting development and Australia can be proud to be involved. At the same time as preparing for our future energy needs, the project is creating jobs, economic activity and hope for the future in the Latrobe Valley, a region bearing the brunt of structural change in the domestic power market.

Developing a hydrogen economy will take decades. Anyone interested in practical advances should support starting now with affordable, available technology.

First published in the Australian Financial Review, 3 February 2022.